“I pushed my soul in a deep dark hole and then I followed it in.” A line sung by the young Kenny Rogers in 1967, the summer of love, over a psychedelic haze of backwards guitar, feedback and acid trips. It brings to mind my first Dunwich Dynamo. If it felt like a journey into the unknown, that’s because it was. Where am I going? Will I make it? Who are all these people? Am I lost? Which way is the sea? Continue reading

Category Archives: Articles

In the year 1949…

The People’s Republic of China is officially proclaimed, following the victory of the Communist Party forces in the civil war.

Winston Churchill makes a landmark speech in support of the idea of a European Union.

George Orwell’s ‘1984’ is published.

Albert II, a rhesus monkey, becomes the first primate to enter space, on a US V-2 rocket, but is killed on impact on his return journey.

Policemen in Liverpool protest about the reduction of the cycle allowance they get for riding their own bicycles on the beat from 5 shillings a week to 2 shillings a week.

Swiss cyclist Armin Von Büren wins the Swiss national track championships as his wheel collapses as he crosses the finishing line in a high speed sprint. The miraculous photograph above freezes forever the split second when Von Büren’s front wheel has collapsed and shed its tyre but he has yet to hit the deck.

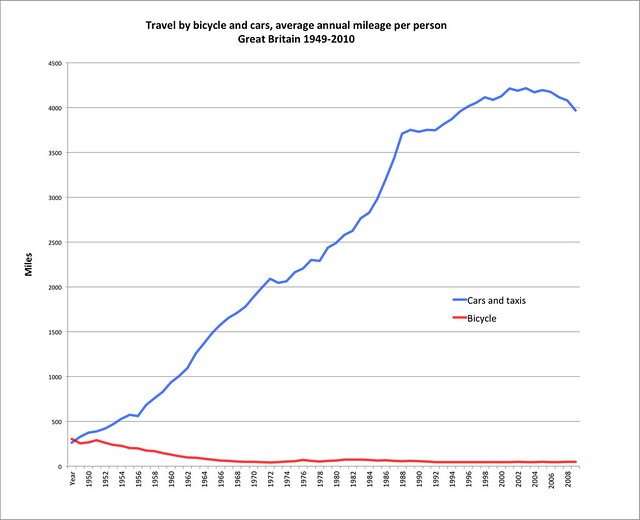

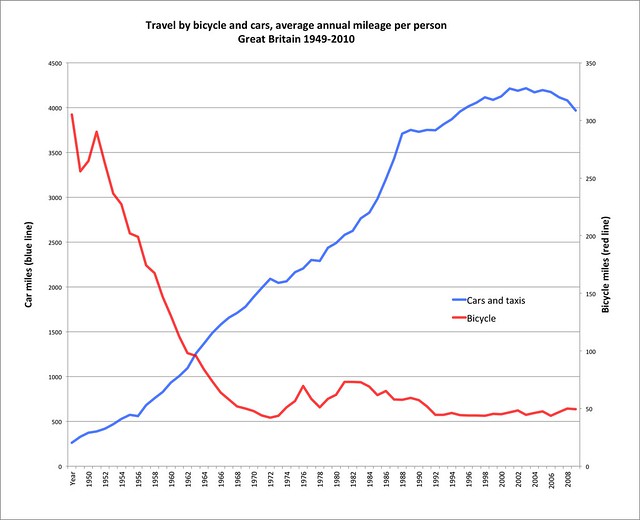

1949 is also the last year in which the British people travelled more miles by bicycle than they travelled by motor car. In that year, on average, people in Britain travelled 305 miles a year by bicycle and 261 miles per year by car. The statistics are from the Department of Transport.

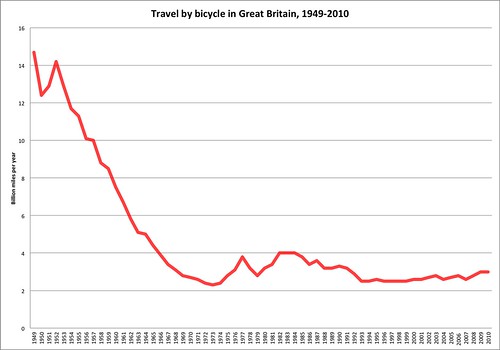

1949 was the beginning of the period of the Great Extinction of cycling in the British Isles. The motor car and the fuel required to move it became steadily more available and affordable. Politicians and planners decided that personal mobility was unequivocally a good thing and that British roads were for cars, not bicycles.

The same figures, but with miles cycled plotted on a separate axis, to aid comprehension:

In 2010, the average distance British people travel by bicycle annually is 50 miles and the average distance they travel by motor car is 3,966 miles.

If, as some suggest, Britain is experiencing a bicycle boom, there is a long way yet to go.

David Hockney, the Bigger Picture and the Aesthetics of Cycle Touring

“You road I enter upon and look around! I believe you are not all that is here;

I believe that much unseen is also here.”

Walt Whitman, Song for the Road

In one of the final rooms of the Royal Academy’s blockbuster exhibition of new work by David Hockney that closed earlier this week there was a video wall showing a series of short films that take Hockney’s 1970s and ’80s photo montages into the digital video age. Using arrays of 9 and 18 video cameras mounted to film a single scene simultaneously, Hockney was looking once again to break free from the single point of view and prescriptive framing that defines photography and film.

In a radio conversation with Andrew Marr, Hockney explains,

“In the end, the world doesn’t quite look like photographs. Cameras give you a certain kind of view, but it’s not quite the human view. With one camera, no matter what it’s like, however high definition it is, you’re going to have one perspective. You cannot escape that and however big you make the picture, it’s going to be same time in the far left corner and the far right. As your eye moves through it, it doesn’t see time. It can’t.”

In his photo montage and film works – as with his painting – Hockney is aiming to achieve a more immersive representation of reality and experience: A Bigger Picture, as the exhibition was titled.

One of the film pieces depicts a slow passage along a country lane. In the opening moments we see a pair of cyclists ride towards the camera array, and past it, behind us. Apart from two film pieces filmed in his studio and featuring Hockney, several of his friends and small corps of ballet dancers, this pair of cyclists on the country lane are the only people depicted in the entire exhibition. We must assume that there is an element of intention here for Hockney’s sometimes flamboyant persona belies a hard grafting master of technique and detail. For me, it seems entirely appropriate as the whole of A Bigger Picture spoke to my experiences as a cyclist – as a cyclotouriste – in ways that I found joyful and uplifting.

Photograph above by Rich Cousins

In the same conversation with Andrew Marr, Hockney talks of moving to the East Yorkshire Wolds having lived for three decades in southern California. It was a homecoming for this is where Hockney grew up and where he had spent thirty Christmases, back from Los Angeles to visit his mother who lived in Bridlington, on Yorkshire’s North Sea coast. Hockney recalls his life as a teenager cycling to and from work along the lanes that have been the subject of his most recent work and are the main subject of A Bigger Picture.

“I worked on a farm. I cycled around here for two summers. I used to cycle up to Scarborough, Whitby, a long way actually. You get to know it, and you know it’s hilly if you’re cycling. I was always attracted to it. I always thought it had a space. One of the thrills of landscape is that it’s a spatial experience.”

He’s no longer riding a bike, but I think he is recalling how the particular sensual, rhythmic experience of travelling in a landscape by bicycle – the kinaesthetic qualities of bicycle travel – contributes to the cyclotouriste’s appreciation of the character and meaning of particular places.

Cycling is a functional mode of everyday transportation but it is also a pastime. Driving a car for pleasure (‘motoring’) was once a common pastime but is increasingly rare. People drive with a purpose or destination in mind. Hockney’s own reacquaintance with the East Yorkshire landscape was through a period of daily car journeys to visit a terminally ill friend. Any enjoyment of the journey is largely incidental to getting from here to there. It’s not hard to see why. Drivers are confined behind the wheel, encased in a small metal box, removed from the elements. Their view is framed and constrained by the windscreen and anyway modern cars travel at speeds that allow only the most fleeting appreciation of the surroundings.

It is by walking (and perhaps swimming) that we achieve the most intimate connection with nature and of place, yet when walking or swimming it is difficult to cover much distance or to experience the changing shape and character of the landscape, to experience it as it unfolds around us. The bicycle is perfect for plugging into the Bigger Picture. A cheap, light, noiseless machine that affords total immersion in our surroundings and enables us to cover relatively large distances with minimal effort. The chief drawback compared to walking is that the cyclist is more confined to roads and byways, whereas the walker has the most freedom to roam at will (especially if prepared to trespass).

The road is a familiar Hockney motif and it is a near constant in these paintings. Roads that twist and turn in extravagant loops, roads that roll cheerfully across the landscape, dipping behind hills and returning to crest the next ridge. Roads that travel through woods, arched over by trees that form arboreal tunnels in which light and dark stripe the tarmac surface. These are roads with personality, even down to their surface which is carefully observed and rendered. In the small number paintings where the road is unseen it is clear that the landscape is being viewed from the road, looking out across a hedgerow or or verge rich with foliage and star-spangled with cow parsley. These are roads where you are unlikely to see many cars. Roads along which cyclists like to ride.

Hockney’s Tunnel series presents the same view of a single green lane lined by trees on each side at different times of year. With its thick grass mohican running down the centre it’s easy to picture a lane like this on any countryside ride.

Like Hockney, the cyclist returns to the same lanes, noticing the changes in the season, the weather, the time of day, variations in light and vegetation. After some years the cyclist would really know that lane very well. It is exciting to adventure into a new places, and ride along untravelled roads, but what cyclists most often find themselves doing is returning to the same places, the same roads, over again. New places can be thrilling, but familiarly can bring with it a deeper understanding and affection for a place.

Photograph above by Simon @ the Unofficial Hockney Trail

After three decades abroad, Hockney has returned to the countryside of his youth, bringing with him the dramatic light and shade and sublime, super saturated pigments of the American West. Along with his gift for composition he puts this luxurious palette to work in rendering the English countryside in a bold new light that is unexpected yet I think utterly faithful to the lived experience of total immersion in the landscape.

The colours, shapes and textures of the English countryside are as exciting as those in southern California or anywhere else in the world. Vast, constantly changing skies, clumps of acid green euphorbia, deep red beech forests, an iridescent woodland carpet of bluebells, banks of hot pink willowherb and perhaps most spectacular of all, the hawthorn blossom that erupts between the coming of spring and the early summer. Hockey dubs this ‘Action Week’, a reference not just to the growth in the hedgerows but to his own relish at being out there and painting them.

This time of year is startling to behold and Hockney brings passion and excitement to his canvasses, to the point of putting off many of the critics. No doubt, it is an escapist, optimistic, romantic vision of the countryside. But I think it is quite honest and no more sentimental than he means it to be. Hockney pastoral. There are no off-motorway distribution centres, fly-tipped rubbish, wind turbines, ‘luxury home’ developments or industrial farming paraphernalia. He is not drawn to the hallmarks of the Edgelands or the Unofficial Countryside beloved of contemporary psycho-geographers. There’s nothing wrong with Iain Sinclair stalking around the semi-derelict industrial estates of the periurban fringe and taking pleasure in their toxic trades, but that’s not what Hockney’s work is about. It’s about experiencing the relentless forces of nature, observing the shapes and colours of the vistas and plant forms and embracing the simple joys of being out there in the wind and the sun and the snow and the rain, the owls and the bats and the blossom and the bees, the trees and the leaves and the fields and the streams. All of which still exists in every corner of this island, no matter what anyone says about concreting over the countryside. It makes me want to get on my bike and ride.

All images are copyright David Hockney (except where otherwise noted) and reproduced for purposes of criticism or review in accordance with Section 30 (1) of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

When a picture is worth a thousand words

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. This photograph, taken this morning on my regular ride to work, won’t be winning any Pulitzer prizes but it does have a lot to say about the state of cycling in London in 2012.

”

” Click to enlarge

In the foreground you can see a row of newly installed stainless steel bike parking stands, made by Cyclehoop, a company founded by the talented architect and product designer Anthony Lau and one of a growing number of small, hip London-based start-ups who are playing their part in current bike boom. At the far end is a shiny new Lezyne track pump encased in a towering column of brushed steel. It is free to use for anyone whose tyres need a top up.

It is all very high specification stuff, and I expect it cost a pretty penny to install the stands and the small expanse of cobblestone paving, but also to remove the pair of traditional black Sheffield stands that previously stood on this site, and can be seen in this image from Google Street View:

Of course, cycling in London is très fashionable and everyone wants their bit of the bike boom. The Times is campaigning for cycling and politicians are falling over themselves to get with the cyclists. They’ve given us subsidised hire bikes and even as they struggle with bruising cuts to public expenditure they are renewing perfectly serviceable Sheffield stands and throwing in top-of-the-range track pumps for good measure.

None of this goodwill goes as far as challenging the primacy of the motor car on the public highway, reducing speeds or re-allocating even a modest amount of road space so that people aged eight to eighty can ride their bikes in safety and comfort. But it’s the little things that count and a stainless steel track pump really shows us that they care, doesn’t it?

To the right of the track pump is a bicycle locked up to the new stands. It’s low end road frame with skinny tyres, deep section rims, mountain bike handlebars. No chain case, no mudguards, no pannier rack and no basket. The chain is poorly maintained and orange with rust. In other words, it is the typical bike offered to the prospective London commuter cyclist by the major London bike shop chains. Look more closely and you’ll see it’s a Claud Butler ‘Criterium’, a 2011 model (now discontinued) whose recommended retail price was £299. It is still available online for less than £250.

Claud Butler was a framebuilder from Clapham, just down the road from here, and one of the giants of British bicycle history. In the days when every London neighbourhood had its own frame builder, Claud Butler’s lightweight racing machines stood above the rest and helped define a golden era of mass cycling in Britain that began in the 1930s, blossomed in the years following the Second World War and lasted until the Great Extinction of the late 1950s when mass car ownership began to consign the bicycle to a marginal, mostly recreational role.

The 1950s Sport Anglais model, pictured below, shows the very finest of the Claud Butler marque. The elaborate bi-laminated lugwork, the partly chromed biplane fork crown and detailed box lining are the height of skilled craftsmanship.

In those days a Claud Butler bicycle would cost a full month’s wages, maybe two. And many Claud Butlers from this era (and later) are still ridden today. Our sub-£250 ‘Criterium’ model makes more modest demands on the cyclists’ wallet for it is a standardised, mass-produced product of the global economy and not build to last. Who knows where it was made, by whom, in what conditions. I draw a little comfort from the thought that somewhere in a far off eastern land, someone cared enough to ensure that the fork, frame and saddle each boast the distinctive ‘lemon and lime’ colourway that any Claud Butler connoisseur will immediately recognise as the distinguishing feature of the 2011 ‘Criterium’.

If he weren’t spinning in his grave, I am sure that Claud Butler, as a former racing man, would share my own doubts about the suitability of the ‘Criterium’ model that bears his name for anyone taking part in an actual Criterium race, such as the London Nocturne, which returns to Smithfield Market this summer, sponsored by IG Group, ‘a world leader in the trading of financial derivatives’. Even the financial whizz kids of the City want their share of the cycling pie.

But I digress. Back to our street scene.

The two cyclists we see are wearing yellow high visibility tabards, standard issue kit for the London commuting cyclist whose major concern is getting home without bodily injury. Not that wearing such a garment will ensure against a lorry crushing you to death under its wheels (click here to read the Coroner’s report following the inquest into the death of London cyclist Emma Foa).

The cyclist waiting at the red light is unusual and I don’t mean because it’s unusual to see a London cyclist waiting at a red light. How so, you might ask. Is this not the archetypal London cyclist? It’s true, he’s one of several hundred thousand people who have made use of the London Cycle Hire scheme (aka Boris Bikes) and, like many other London commuting cyclists, he’s sporting a helmet and a casually cycle-specific outfit comprising of a pair of baggy black shorts and the aforementioned high visibility tabard. But it is the combination of these two choices that makes our man a most unusual sight. Overwhelmingly, people riding Boris Bikes wear neither helmets nor high viz and find their normal clothes more than up to the task. Most often they ride in a smart suit and tie, sometimes in a long, flowing flowery dress and occasionally a pair of velvet loon pants. In short, people on Boris Bikes wear their everyday wardrobe, whatever that may be.

While their contribution to London’s overall transportation mix has been minimal, the 8,000 subsidised Boris Bikes have done more to promote the possibility of everyday cycling in everyday clothes than any amount of cycle chic blogging, tweedy runs or state-sponsored bicycle catwalk shows. Boris Johnson, our dishevelled, tousle-haired cycling Mayor is as good sartorial ambassador for everyday cycling as you could expect to meet. Unfortunately, he is also the person with the most real power to improve London’s roads for cyclists yet he thinks that it’s fine to cycle down the Euston Underpass or around the Elephant and Castle roundabout, as long as you keep your wits about you and he thinks that the best way to make London a world class cycling city is to splash a lot of blue paint around.

Returning to the photograph, you’ll notice that unlike both of the cyclists, the large black minivan has no high visibility overgarments or markings.

An observant reader tells me that this is one of the new style London taxis made by Mercedes Benz. Its driver clearly doesn’t care much about his own safety on the road, preferring jet black for a sleek, stealthy, Knight Rider look. Nor does he care much about the safety of others, including our pair of safety-conscious cyclists. Not only content with occupying the 5 metre long cyclists’ Advance Stop Zone he has encroached a further metre over the stop line towards the pedestrian crossing. There is a large police station very close by to where this photograph was taken, but the taxi driver need not concern himself as according to this London barrister the police have a ‘total tolerance’ policy in relation to this kind of traffic law violation, as most drivers know.

Thanks to the taxi driver’s casual indifference to the rules of the road, the Boris Biker is perfectly placed in the vehicle’s blindspot, ready to to be tipped off his bike should the taxi turn left when the traffic light turns green. Let’s hope it is on its way west towards Kennington and not south towards the Elephant and Castle gyratory system towards which the cyclist in the middle of the crossing may well be heading. You may want to wish her luck for at the Elephant and Castle she will find herself in no doubt that whatever the politicians say about a cycling revolution, no matter how many stainless steel track pumps appear like futuristic mushrooms on London street corners, we are still deep in the period of the Great Extinction of cycling. And there is a long way still to go.

Red Flag, Yellow Flag

Oh, how the tables have turned.

In the late 19th century, people looked with alarm at the new ‘horseless carriages’ that were appearing on the public highways. Governments on both sides of the Atlantic responded by passing ‘red flag laws’ to regulate this new and potentially dangerous form of transport.

In the UK, the Locomotive Act of 1865 required motor vehicles (mostly steam engines at that time) to be led by a pedestrian, waving a red flag or carrying a lantern, to warn bystanders of the vehicle’s approach.

According to Wikipedia Quaker legislators in Pennsylvania unanimously passed a bill through both houses of the state legislature, which would require drivers of “horseless carriages”, upon chance encounters with cattle or livestock to

-

(1) immediately stop the vehicle,

(2) “immediately and as rapidly as possible… disassemble the automobile,” and

(3) “conceal the various components out of sight, behind nearby bushes” until equestrian or livestock is sufficiently pacified.

The bill was vetoed by Pennsylvania’s governor.

With the coming of the internal combustion engine, steam gave way to petrol-power and a new breed of ‘automobiles’ took to the roads. The UK Parliament repealed the red flag law in 1896 and raised the speed limit from 4 mph on country roads (2 mph in towns) to 14 mph. Motorists celebrated with an ’emancipation run’ from London to Brighton, an event that is still commemorated in by a vintage car rally.

More than a century later and in the town of Kirkland, Washington, it is pedestrians who are encouraged to carry yellow warning flags when crossing the road.

Sergeant Mike Murray of the Kirkland Police Department is in no mistake about who’s to blame when a car runs down a pedestrian in his town:

“we had 62 car-pedestrian collisions in the city and of those 62, none of them were carrying a flag”

Progress, eh?

But don’t be downhearted. The fightback is underway. And it’s deliciously subversive:

Blackfriars Bridge: how far to push the limits of peaceful protest?

In the face of a unanimous motion of the London Assembly and the Mayor’s own misgivings, Transport for London plans this weekend to build a dangerous new gyratory on the north side of Blackfriars Bridge, a road scheme that has been criticised from all sides for putting the interest of private motor vehicles ahead of the pedestrians and cyclists who, taken together, will be the majority of the road’s users.

The Mayor’s ‘ambassador for cycling’ is Andrew Boff AM. He recently had this to say:

‘I am staggered that so many cyclists use Blackfriars Bridge, if it was on my commuting route I wouldn’t because it is too dangerous. I hope a full review of the new layout and speed limits on the bridge and the publication of all the relevant data will result in a sensible solution that will address the needs and safety of all users.’

Unfortunately TfL’s head of surface transport Leon Daniels has stuck up two fingers to Mr Boff and everyone else and are ploughing on ahead with the new gyratory.

TfL’s contractors aim to have the job done by Monday, so as not to have works going on at the same time on Blackfriars and the neighbouring Waterloo Bridge. Waterloo Bridge is currently in the middle of six weeks of roadworks by British Telecom. As Leon Daniels says in the TfL press release:

‘In order to keep disruption to Londoners to an absolute minimum our contractor will be working 24 hours a day from the evening of 29 July to the morning of 1 August, thereby getting the work done in the shortest possible amount of time and avoiding clashing with other planned bridge works in central London.’

The Blackfriars Bridge flash rides planned for Friday night are all very well for expressing opinion but are unlikely to keep the bulldozers at bay. However, if sufficient riders were to linger awhile, say for 48 hours, until Monday morning, they might just prevent access to the site by TfL’s contractors. TfL would have to reschedule the work, rebook the contractors, and so on. The delay might mean the Mayor would take notice and do something, rather than just talk about making London better for cycling and walking.

Alternatively, if word got around that something was brewing, and the Mayor decided to bring in squads of Police to guard the bridge, it would become very apparent that he was heavy handing a situation in the face of overwhelming public and political opposition. That would not be very good PR.

It would require a significant number of people to be prepared potentially to put themselves in harm’s way, possibly sacrificing a few D-locks and risking arrest for obstruction of the public highway. A couple of months ago on the radio show Jenny Jones AM, the Green Party’s candidate for Mayor, said she hoped she would not have to resort to lying down in the road to prevent TfL’s scheme.

I guess we’ll see how strong opinion really is among London’s cyclists who are rapidly learning that in Transport for London, we have a formidable enemy.

How to follow the Tour de France on TV, twitter, newspapers, blogs and podcasts

Pity Lionel Birnie. For the cycling journalist and regular Bike Show contributor, following the Tour means being stuck in a smelly Skoda with three other hacks for 5+ hours a day, living out of a suitcase, sleeping in tatty hotels with paper thin walls (if he manages to find a hotel room at all) and getting fat eating junk food (all the more galling in the land of haute cuisine). He’ll get a few fleeting glimpses of the racing, but mostly he will be stuck in traffic jams, waiting around in the press centre and trying to get a few moments of face time with knackered or nervy riders who’d rather express themselves on twitter than submit to the questions of a seasoned sports journalist.

For the rest of us who are not part of the media caravan, and thanks to the efforts of a legion of Lionel Birnies, we are spoilt for choice. Here are a few suggestions for getting the most from following the three week festival of cycle racing, the world’s biggest annual sporting event on its grandest stage. Continue reading